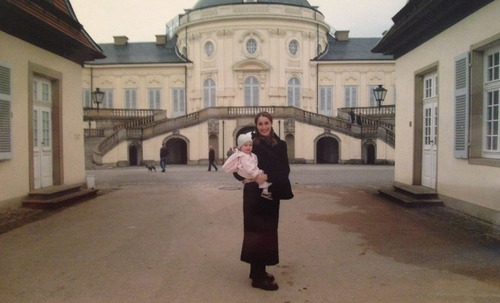

There is an aspect of being a father as a familiar figure, it is natural to the process but peripheral for some. Simone was born in the same set of circumstances that have dictated our parenting life–in distance. Lori gave birth in Virginia and I was teaching in New Jersey. I made it on time to be part of the birth experience as much as I could be part, to observe and document. Giving birth changed everything for us because distance was always a factor, 7 hours commute didn’t make it easy. Under those circumstances the European attitude of having the father also on parental leave makes sense. But in fact, Lori didn’t even get paid parental leave. For me my studio is where I am, I work with what I have, so I never felt limited by lack of access to the studio. Lori and I never stopped doing what we planned to do, Simone was three weeks old when we presented our work at a conference in Atlanta and the organizer was rocking Simone while we talked. But what really helped us was a residency in Germany. Lori, Simone, and I were in Germany almost a full year in a castle in Stuttgart. Simone learned to walk there and we traveled together in Europe. There was always an inclination to make the kids (now two, Ian was born in 2006) part of our academic, research life. Both of them have been exposed to lectures in migration and anthropology, as we didn’t have babysitters or they were sick and we happened to be in different places. They confess they don’t particularly like that, but they got used it. A year ago, Simone presented my work at an opening because I was was away doing an lecture. Being part of our family means being part of every aspect of our lives.

-Edgar Endress

Simone and Lori

This post is part of the (Pro)Create Anthology, a collection of narratives about the intersection of professional studio practice and parenting.