Rebecca Silberman“12 x 12” 2002-2013 (on-going)

Postcard image with one portrait from each year, 2002-2013

Postcard image with one portrait from each year, 2002-2013

On roughly the same day each month for nearly 14 years, I have made a full body portrait of my daughter, Rosalee, on a black backdrop, spanning from newborn to, now, a young woman. The project, which was first exhibited in early 2014, a month after my daughter Rosalee turned 12, consisted of 144 8” x 10” tintype plates. While this started out as something I intended to pursue only during my daughter’s first year of life, it quickly developed into a compulsion of record-keeping, which also includes notebooks full of writing and drawings.

Many people are curious about my daughter’s cooperation in all of this. It was not until she asked a classmate when she was little when their “Portrait Day” was that she had any inkling that other children were not compelled to sit for monthly portraits as a matter of being alive. Both she and my husband are (sometimes reluctant) collaborators. My vision is to create a consistent and authentic record of a single individual’s passage not just from birth through adolescence, but over the course of a life time—for as long as it can be sustained. It is not so important that I make these, only that the project continues, perhaps even by (sometimes reluctant) grandchildren or other collaborators.

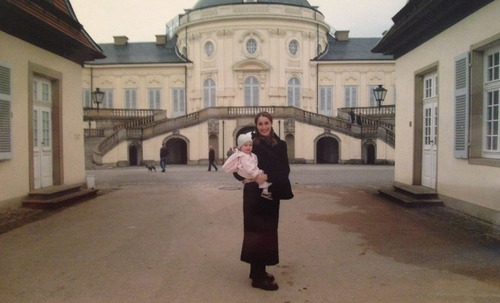

Rosalee, 3 months

Rosalee, 3 months

This project is an archive of tintypes not for its own sake, but because in the now largely forgotten vernacular, bigger tintypes were often copies of smaller tintypes, intended to be framed and placed on view—often of someone who was deceased. So they are a sort of signifier of passing. When these plates have been exhibited, I have also displayed alongside this personal archive a small sampling of large copy tintypes of babies that I have collected over the years. Many of these include clear indications that they are copies. It is not uncommon to be able to see nails around the periphery, holding the smaller plate in place. Sometimes they have been re-photographed in the original mat, which is evident. Often they are retouched with parts of the image background altered and details painted in. More than likely this made the portrait into more of a small painting to be put on permanent display.

-Rebecca Silberman

Rosalee, 37 months

Rosalee, 37 months

Rosalee Kelly, On being photographed by her mother every month since she was born

How would I describe this project? My mother has taken a picture on me on or around my un-birthday (the 8th of each month) since I was born. At almost 14 years old now, we have not missed a single month.

It didn’t seem that it would add up to be something as large as it did. What I mean by this is the fact that I used to go along with it without a thought to what it would turn out to be project wise. When I saw the 12×12 project (exhibited in early 2014, just after I turned 12), it was suddenly something big and important, like a long series of books. I mean these photos documented the years and months and days of my life. The best way to describe them would be a visual diary of my existence. Someday they might not have any context, so they won’t really be an emotional representation of my life, (save the fact I start to smile less as the years progress), but as of now, they show the extent of my physical growth and maturity and with help from my mom, they have some emotional context too.

Rosalee, 105 months

Rosalee, 105 months

I have been asked before if I wanted to stop this project. I think we are a little bit too far down the rabbit hole for that now. We are way too far into this project to quit now, and eventually the focus of this project will be handed to my daughter from me and the cycle will start all over. Now that I am older, I have started to help my mom with this monthly process. I help her with the set up and have even learned to do some of the old processes that my mom teaches and loves so much. I have learned to assist making a wet collodion tintype plate. My mom says that my ability to hold still for a long time in front of the camera borders on the supernatural.

Rosalee, 141 months

Rosalee, 141 months

My favorite images are the probably the most recent ones because I now no longer look at all like a child. I like looking at all the older ones too because sometimes I don’t even remember them being taken, but they were and they are now a part of my life. I have a record of what I looked like at every stage.

-Rosalee Kelly

Visit Rebecca’s Website

This post is part of the (Pro)Create Anthology, a collection of narratives about the intersection of professional studio practice and parenting.

This post is part of the (Pro)Create Anthology, a collection of narratives about the intersection of professional studio practice and parenting.